Driven by choice

Art revels in its preference- and perspective- driven identity. It is dictated by choice. Choice made by whom, one may ask? Quite easily, all those involved. Much like what Mahati and Manasvini said, an interpretation is the articulation of an internalized experience, and is therefore highly subjective. In a painting, one sees a shade of blue. The painter, when he was painting it, identified it as cerulean blue. On the other hand, a viewer thinks it to be Prussian. Who is right? More interestingly still, does only one of them have to be? What definitely counts for an aware and informed discussion about the understanding of what this shade of blue is, is how dispassionately and convincingly both sides can present personal stances and justify their answers. This is not unlike the dancer choosing to be either a creator or an interpreter at a given moment (or even choosing to be a bit of both). Similarly, a member of the audience may see an independent creation, or see an interpretation of the musical or lyrical content while witnessing a presentation.

Another thought that comes to mind here is the default bias that audience members exercise thanks to their individual life experiences. Remember the small clip we shared of Kelucharan Mohapatra ji (Newsletter Issue 2 – Dance – Infinite in the moment?) performing a piece of Abhinayaa to Jayadeva’s Geet Govindb? Through his Abhinaya, he created a Vrindavanc of great beauty. He likely used images from his environs to inspire the movement and mood he painted on stage. Here’s some food for thought: When all of us watch it, do we see the exact Vrindavan Kelu ji’s mind’s eye must have seen? Do we see trees and creepers and a smiling Krishna just the way he imagined it? Not really. We inherently add our own twist to it, without consciously meaning to. He leads us into an intellectual and emotive space that is intrinsically enmeshed with our visual memories. Remember the dense bougainvillea creepers that sit draped on your neighbour’s wall? When Kelu ji gracefully twirled his hands as if to mimic a dainty creeper, your mind might have ambled back to them. And Jayadeva? He had probably envisaged it very differently, which he subsequently captured in words. With so much room to create and absorb an incident idea, how each of us translates, interprets and reflects it is quite a complex and nuanced phenomenon to appreciate.

In a painting, one sees a shade of blue. The painter, when he was painting it, identified it as cerulean blue. On the other hand, a viewer thinks it to be Prussian. Who is right? More interestingly still, does only one of them have to be?

An extended consciousness

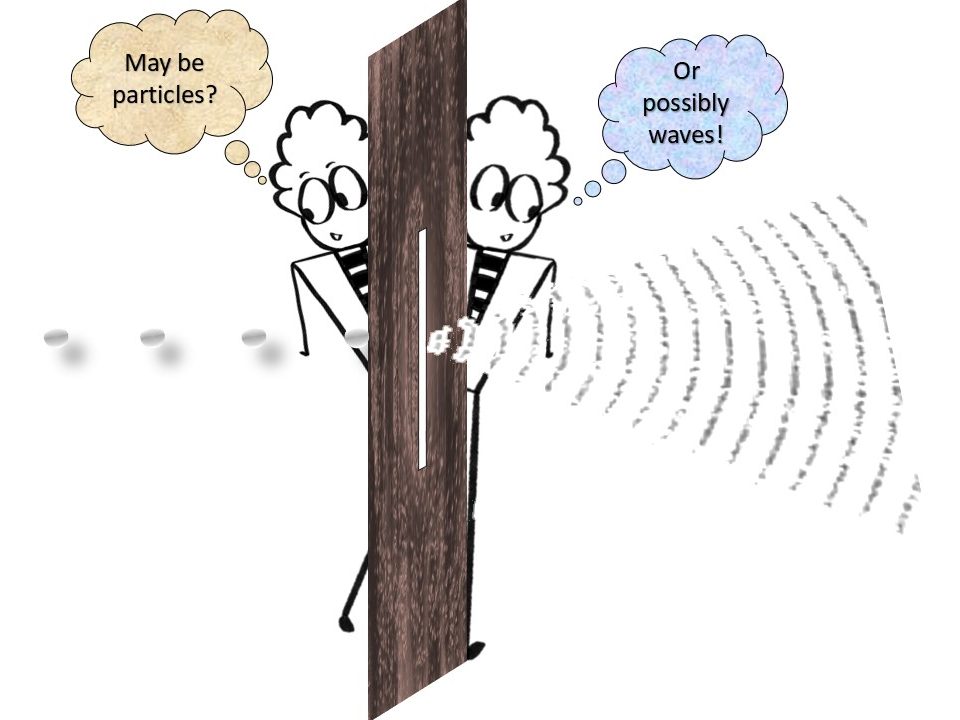

Does the identity of the dancer oscillate like a pendulum between two distinct states of creation and interpretation which remain perpetually non- convergent? Or are all his/her phases, whether transient or long lasting, existent within an ever-expanding spectrum of his/her state?

An interesting leitmotif that kept emerging from our speakers at the Dance Debates was the curious idea of self-reflection. At any random minute in a dance recital, the dancer finds him/herself coexisting in different states of mind. ‘Do I remember how the next Nrittad sequence commences? Has my eyeliner started running because of the sweat?’ These are some of the more concrete, accessible (and dare I say, objective) questions that make the rounds in the dancers’ heads. Slightly trickier ones are those that pose a challenge even at the articulation stage. ‘When I play a Nayikae, do I become her? Or do I briefly inhabit her skin, and emote what she feels because I seem to understand her character?’ Even more difficult is to determine for oneself where these two previous questions diverge. And that is precisely the same struggle with the creator/interpreter conundrum. ‘I seem to exist and operate at various points across a wide range with these two as its extremes, without really knowing for sure what measure of my current state identifies as one or the other’. Finally, there is the rather indescribable, visceral knowledge that our questions surrounding the state of creating/ interpreting are just a fraction of a bigger whole consisting of questions surrounding emotional and objective states, and spatial, literary and musical awareness amongst others.

Metaphor x Metonymy

The concept of a metaphor strongly drives the interpretative character of dance. We reference a relatively unknown object to something that we were previously well familiar with. Think of a dancer portraying an elephant on stage. Going back to what Manasvini and Mahati spoke of in the Dance Debates, the aspect of imitating that which we see around us (Anu Karana) and presenting it through the medium of our physical bodies on stage is a big part of dance. When we see a dancer portray characters, human emotions or tendencies we recognize from our lives outside of the auditorium, we experience the metaphor-centric, interpretative identity of a dancer. The dancer is evoking a memory-based cue from the viewers, thereby encouraging them to draw a similarity. He/she will then progress the narrative with the assistance of this evoked cue.

In his seminal work in linguistics, Roman Jakobson stated his belief that language was basically bipolar in structure, and oscillated between the poles of metaphor and metonymy. This helped personally concretize two ideas: one, that dance is essentially language; and two, that it too, oscillates between the states of creation and interpretation at all times.

In contrast, a metonymy is more of a self-reference. A small part of a larger concept is highlighted and recognized as an identifying factor of that concept. Just a mention of this is enough to represent a wider or larger concept.

To elucidate an example, let’s think back to a section of ‘Millennial Adavusf’, a lecture demonstration that we had shared previously (Newsletter Issue 2 – Dance – Infinite in the moment?). The choreography of a jatig for a production based on the life of Lord Krishna sees artists Shweta Prachande and Apoorva Jayaraman weave in movements that are reminiscent of dance steps seen in a typical Raas Leelah. They do not transform the jati completely into a Raas Leela – like sequence. Instead, they retain the grammar of the Bharatanatyam form and employ traditional hastasi and adavus to lend even the Nritta a hint of the theme of the literature handled in the verse. The jati, like any other, is devoid of verbal meaning, and is purely a rhythmic structure. But by the intelligent use of inspired movement, the dancers use the otherwise pure dance sequence to maintain a continuity of the literary theme. Does the jati share a proximity with some Raas Leela derived movements? Yes. But this isn’t coincidence, and nor is it deliberately orchestrated. This is proven when we ask ourselves whether we would have gleaned the Raas Leela connection in this jati had we not been made aware of it expressly. Even if we were unfamiliar with the concept or visual representation of a Raas Leela, the jati would have made aesthetic sense from a pure, standalone Bharatanatyam perspective. And secondly, it would have evoked a sense of merry making and fun, which is what the Raas Leela is essentially all about. That is the metonymy in dance. And it speaks of the creator in the dancer because the inspiration to augment even the seemingly disconnected parts of a piece with the fragrance of meaning comes from within.

In his seminal work in linguistics, Roman Jakobson stated his belief that language was basically bipolar in structure, and oscillated between the poles of metaphor and metonymy. This helped personally concretize two ideas: one, that dance is essentially language; and two, that it too, oscillates between the states of creation and interpretation at all times.

Einstein said, “After a certain high level of technical skill is achieved, science and art tend to coalesce in aesthetics, plasticity, and form. The greatest scientists are always artists as well”. Only when we know the grammar, science and the beautiful multiplicity of our identities can we hope that art flows from and through us. It is only then that we can hope to become simultaneously, both the artist and the art.

GLOSSARY

a. Abhinaya: Literally meaning "to carry forward", abhinaya is the craft of narrative and emotional communication through the use of facial expressions, hand gestures, body language, lyrical and musical content, and costumes.

b. Geet Govind: The Geet Govind is a work composed by the 12th century Hindu poet, Jayadeva (Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2013, June 27). Gītagovinda. Encyclopedia Britannica. )

c. Vrindavan: A town in the state of Uttar Pradesh in northern India.

d. Nritta: It is one of the three main aspects of Indian classical dance forms (the other being Nritya, or interpretative dance, and Abhinaya, or the drama element of dance). It is the primary visual distinguisher of each style, thereby helping them establish a unique movement identity. Creation of geometric patterns on the floor and in space, and definition of elaborate movements for the major and minor limbs of the human body constitute the bulk of its purpose.

e. Nayika: A Sanskrit term used to denote the female protagonist in dance or drama.

f. Adavu: Adavus are like the alphabets in Bharatanatyam - a set of basic movement units one is taught while starting to learn. In the way it is taught it formulates building blocks of some kind using which complex movement units are later assembled in choreographies. Read a more detailed account on Adavus by RootEd here.

g. Jati: A standalone Nritta sequence comprising of rhythmic phrases woven together into a pattern. The duration and intricacy of a jati is determined by its placement within a composition, although the intention is to offer rhythmic respite to both, dancer and audience during compositions that have high emotive and literal value.

h. Raas Leela: A folk-dance form popular in many parts of north India (Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "rāslīlā". Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 Dec. 2013).

i. Hasta: Hand gestures that are employed in Bharatanatyam both for aesthetic effect as well as to convey meaning. Read a more detailed account on hastas by RootEd here.