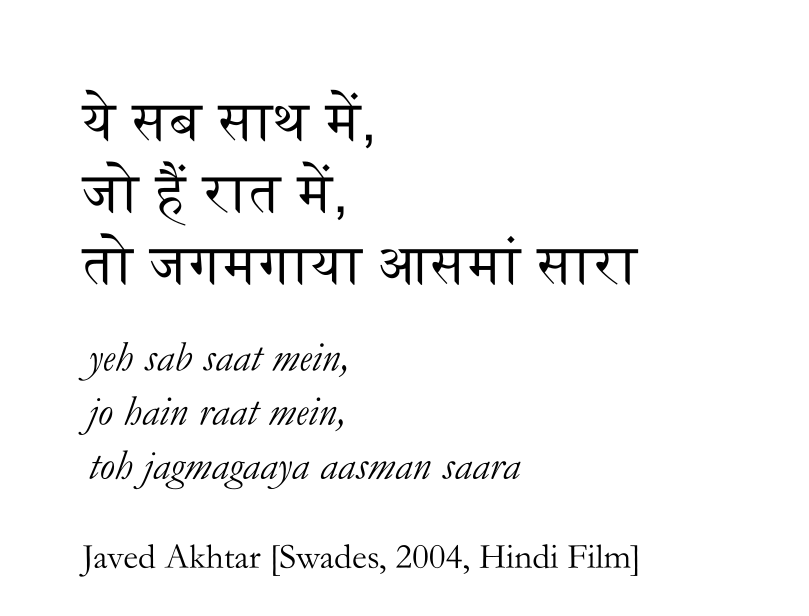

A million brilliant stars, lighting up en masse the darkness that is the night!

With so much conversation surrounding the ushering in of representation of the vast and awe-inspiring diversity that we see around us every day, inclusivity becomes not just a subject of great importance but a living, breathing component of our lives.

“Characterized by including a great deal, leaving little out,” c. 1600, from Medieval Latin. The Middle English adjective was incluse “confined, shut in” (late 14c.).

Inclusive: How?

We read the meaning the dictionary gives us, we comprehend the etymology, we interpret the words, we string together a sense of the word.

‘Could you share an example of how it reflects in dance?’

Faced with the question, I found myself clutching a further bunch of questions, the poorest of which (from the angle of English grammar, that is) was ‘inclusivity how?’ It isn’t for the lack of examples that most of us struggle to cite examples on the fly. It is more because there are so many layers to this word that picking an instance from any one of them is quite a challenge.

What, one may ask, are these layers that most practitioners will think of when they are posed the inclusivity question? Since our arts are highly nuanced, offering even an overview of these requires a head scratch. Broadly speaking though, it would be safe to address it on the levels of delivery and reception. As such, these become the responsibility of the artist and audience respectively, with each having their queries to one another on how they may make the entire ecosystem more wholesome rather than dissected.

As artistes, it is initially rite of passage, and later, second nature to lean towards traditional compositions that we inherit through our schools of learning. These pieces are monuments of the thought process, stories, and value system that our nation held close to its bosom as Bharatanatyam blossomed into its current self. It becomes important to understand that content of any kind, is inspired, affected and moulded by the surroundings it was born in. The Margam crystallized into its current form primarily at the hands of, first, the Tanjore Quartet, and over time, the many, gifted Nattuvanars and Gurus of pre- and post- independent India. What we see in a traditional repertoire, therefore, is heavily influenced by the contemporary thought of the time.

Emotion vis-à-vis its perception and representation

The late Paul Freund, one of the most respected constitutional law scholars of the 20th century, once said that the courts of law “should never be influenced by the weather of the day but inevitably will be influenced by the climate of the era.” It would not be inappropriate to also extend these wise words to the culture of art practice. How we understand dance, drama, tradition, literature and culture is, and will be, a continually evolving process. What stays front and central to this evolution is the irrefutable fact that dance is a primal reflection of our emotive bodies. It is a joyous, fully permeable membrane of feelings.

Over the years that it has evolved, have we unconsciously arrested the growth of this quality of Bharatanatyam? No! It remains, as ever, a dynamic tool, a paint brush that allows us to construct, to sketch our innermost sentiment. In that sense, it has always been very open and inclusive. What has determined how it has come to be perceived is the artistic choices that the dance community has made (which is to say, how certain emotions have been explored more widely and at a greater depth than others).

One belief however, remains constant: The general intention of a performance, production or Margam has been driven by Bharata’s Rasa Sutra– A satisfying dance experience is that which evokes a response borne out of emotion in the mind of a viewer. It is grand; cinematic, almost. A swelling interlude of percussion quickens our pulse as a Jatayu struggles to deter a Ravana from abducting a panicked Sita. We also find ourselves holding our breaths as we see the portrayal of a young woman walking back home alone down a lonely street in today’s time. Fazit? Bharatanatyam, of all it is and promises to be, is rudimentarily a voice of emotion. No matter where we go in the world, this will always stay relevant.

Are we therefore (before we ask ourselves the next question), still being inclusive, in spite of the stories we most majorly portray on stage? Yes, because all humans will respond to an emotion similarly. It is interesting to hear what dancers Nitya Narasimhan and Surabhi Bharadwaj spoke about this in our very first Dance Debates.

GLOSSARY

Margam : The word itself means 'path'. It refers to the sequence of songs/pieces that is performed as part of a solo Bharatanatyam concert today.

Nattuvanar : In this context, the term refers to the male teachers who formed part of the ecosystem of dance during when it was still practiced by hereditary dancers. They not only conducted the performances of their pupils by providing vocal and rhythmic accompaniment, they also taught and composed dance within the system.

Tanjore Quartet : Brothers Chinnaya, Ponnayya, Vadivelu and Sivanandam who hailed from Tanjavur/Tanjore, lived during the 19th century, and made seminal contributions to the field of Bharatanatyam and Carnatic Music.

Guru : In this context, the term refers to the teachers of the dance form.

Bharata : Considered the author of the ancient Indian treatise on dramaturgy - The Natyashastra, dated approximately between 200BCE and 200 CE.

Jatayu, Ravana, Sita : Characters from the Indian epic novel Ramayana.